While Chevron is a household name, the 280 “Chevron” companies in Delaware and nearly that many “Chevron” companies registered in Bermuda likely are not. To become global powers, oil and gas majors like Chevron have built a complex web of shell companies in tax havens like Bermuda and Delaware, allowing them to design tax structures that shift and maximize profits, often at the expense of taxpayers around the world.

While losses for taxpayers have been well-documented, actual violations of tax laws have often been difficult to prove. For years the structures that allowed oil and gas companies to pay almost no taxes in countries like Australia had gone unchallenged, presumed to be legal, albeit “aggressive” practices. In 2015, however, a case in Australia found that Chevron’s strategy of intra-party financing wasn’t just an “aggressive” tax practice; it was tax fraud worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

While oil and gas companies have often argued that their use of tax havens and shell companies is perfectly legal, this landmark case against Chevron suggests that oil and gas industry whistleblowers may need to help regulators identify where else in the world oil and gas companies could be fraudulently avoiding taxes.

Whistleblowers like Bradley Birkenfeld have been instrumental in uncovering secretive tax avoidance schemes like this one. Strong whistleblower reward laws provide protection and rewards to incentivize more whistleblowers to step forward. In the U.S., the Internal Revenue Act incentivizes whistleblowers from around the world to report violations of U.S. internal revenue laws and the underpayments of taxes to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS).

If you need help or want to contact an attorney, please fill out a confidential intake form. To learn more about how NWC assists whistleblowers, please visit our Find an Attorney page.

Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Taxation

The Gorgon project at the center of the controversy was built to be one of the world’s largest LNG projects. As the largest single-resource development project in Australia’s history, the project was supposed to bring tens of billions in tax revenue. Yet, between 2010 and 2014, Chevron paid only USD677 million in taxes and, in 2015, the company claimed a USD5.7 million refund. As the promised tax revenue failed to materialize, media investigations, pressure from unions, and a report from former Shell executive Michael Hibbins pushed the Australian Tax Authority (ATO) to investigate.

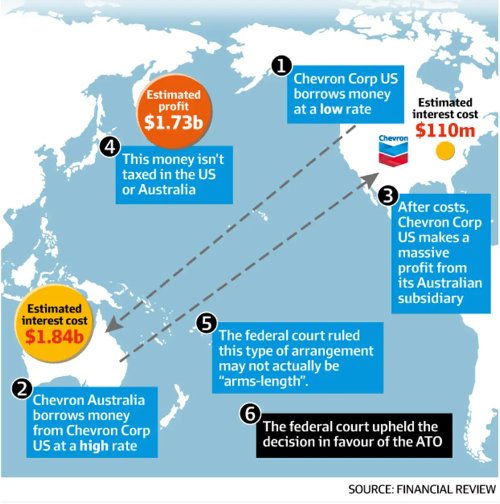

According to the investigation, Chevron used a subsidiary in Delaware to borrow USD2.5 billion, at 1.2% interest and then lend it to another Chevron subsidiary, Chevron Australia Holdings Pty Ltd, at 9% interest to fund the Gorgon project. The high interest rate on the debt reduced taxable profits in Australia by allowing Chevron Australia to claim interest payments as deductions. Through the loan, the Delaware subsidiary made USD1.1 billion in profits that were not taxable in the U.S., and then the company paid back the profits to Chevron Australia as tax-exempt dividends.

In a major victory for the ATO, Australia’s Federal Court unanimously found that Chevron had violated transfer pricing provisions of Australian tax legislation. The Court found that the 9% interest rate was too high for the loan to be an independent arm’s length loan. In May 2017, Australia’s Court of Appeals upheld the Federal Court’s decision. In 2018, Chevron paid a partial settlement of USD654 million dollars, one of the largest tax bills in Australian history.

Key Takeaways

While the ATO’s case against Chevron could set a precedent for other multinationals in Australia, it also revealed a much deeper problem with international tax practices. The case was part of a larger Australian Senate inquiry into tax avoidance in the oil and gas industry related to offshore reserves on the North West Shelf, and the case against Chevron was accompanied by similar investigations into Shell and BHP, as well as an ongoing case involving a transfer-pricing scheme at Glencore, originally revealed in the Paradise Papers. According to former Shell executive Michael Higgins, Chevron’s behavior is one part of a growing pattern of oil and gas companies using non-arm’s length deals with subsidiaries to shift revenue out of high tax regimes, a pattern enabled by major auditing and accounting companies.

Chevron’s tax scandal in Australia is also not likely to be the last. In 2018, the International Transport Workers Federation filed a complaint with the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the European Commission accusing Chevron, among other North Sea oil and gas companies, of tax avoidance on a massive scale. According to the complaint, Chevron used shell companies in the Netherlands to route tens of billions to overseas tax havens like Bermuda and Delaware. The results of the ATO’s investigation into Chevron, combined with subsequent investigations and serious ongoing allegations, raise questions about where else oil and gas companies could be employing similar schemes to avoid taxes.

Whistleblowers have played a pivotal role in revealing some of the world’s most significant tax evasion scandals, including the Panama Papers and the revelations about the Swiss banking system. As the energy transition puts increasing financial pressure on unprepared oil and gas companies, making fraud more tempting, whistleblowers could play an crucial role in revealing more fraudulent schemes. Using powerful transnational pathways like the IRS whistleblower program, whistleblowers can help detect and prosecute tax evasion by oil and gas companies, while protecting their identities and qualifying for a financial reward.

To read about the IRS whistleblower program in more depth, read The New Whistleblower’s Handbook, the first-ever guide to whistleblowing, by the nation’s leading whistleblower attorney. The Handbook is a step-by-step guide to the essential tools for successfully blowing the whistle, qualifying for financial rewards, and protecting yourself.