Following the savings and loan crisis in the 1980s, the Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) was enacted in 1989 to strengthen banking fraud enforcement. The Act allows the Department of Justice to sue banks for various crimes by lowering the standard of proof and extending the statute of limitations set forth in earlier bank fraud law. Under FIRREA, banks can now be sued for making false statements in books and records or in loan applications or overvaluing securities, among other violations.

The following year, Congress enacted the Financial Institutions Anti-Fraud Enforcement Act (FIAFEA), which allows whistleblowers to report violations of FIRREA and qualify for a reward. Unfortunately, rewards for FIRREA whistleblowers are capped at USD 1.6 million, against the best practices of whistleblower law. .

This cap prevents the DOJ from providing meaningful incentives to high-level executives to report fraud, dramatically reducing FIRREA’s impact compared with other powerful whistleblower laws like the False Claims Act and the Dodd-Frank Act.

After the financial crisis in 2008, FIRREA became a powerful anti-fraud tool, facilitating prosecutions that led to major settlements, including a USD 4 billion Citigroup settlement and a USD 16.6 billion Bank of America settlement. FIRREA has also been used to fight misleading claims about emissions in auto lending and other types of financing.

While these settlements demonstrate FIRREA’s potential, the low rate of whistleblower reports reveals that FIRREA has significant room for improvement. In February 2021, the Whistleblower News Network published new data from the DOJ, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) inquiry, showing that the lack of whistleblower cases from FIRREA is “nothing short of a disaster.”

The documents reveal that, since FIRREA was enacted, there have been only six settlements in total. These six settlements brought in USD 19.9 billion in fines, but due to the cap on rewards, whistleblowers received only USD 9.3 million.

The National Whistleblower Center (NWC) is calling on Congress to reform FIRREA by increasing the upper limit on whistleblower rewards to up to 30% of the sanctions imposed, in line with other successful U.S. whistleblower rewards program like the False Claims Act.

With a rewards program that truly incentivizes whistleblowers to step forward, FIRREA has the potential to bring in billions in sanctions, deter fraud and provide a financial lifeline for banking executives who are considering becoming whistleblowers and fear retaliation and loss of career opportunities.

How FIRREA compares to the False Claims Act

Reward laws are crucial for incentivizing whistleblowers to step forward with information about financial fraud. By compensating whistleblowers for their contribution to successful prosecutions, these laws can alleviate risks to whistleblowers’ careers and financial stability.

However, they can only be successful if the rewards are meaningful enough to incentivize high level whistleblowers to take the risk of reporting. The negative impact of FIRREA’s low reward provision can be seen by comparing FIRREA to the False Claims Act.

Under FIAFEA, “[t]he declarant shall be entitled to 20 percent to 30 percent of any recovery up to the first $1,000,000 recovered, 10 percent to 20 percent of the next $4,000,000 recovered, and 5 percent to 10 percent of the next $5,000,000 recovered.”

In practice then, if the government recovers $10 million or more, the whistleblower award would range between $850,000 to $1.6 million – potentially only a tiny fraction of what is recovered by the government. Additionally, a whistleblower who is denied a reward or given a low reward cannot appeal that decision in court.

Meanwhile, under the whistleblower provision of the False Claims Act, whistleblowers whose original information leads to a successful prosecution are entitled to a minimum payment of 15% of the collected proceeds and a maximum payment of 30% of collected proceeds. Within this range, rewards are determined based on the whistleblower’s contribution. There are no caps on rewards. Additionally, if the government refuses to pay the mandatory reward, the whistleblower can challenge that denial in court.

FIRREA was enacted several years after the False Claims Act’s whistleblower amendment was added in 1986. Yet, while FIRREA has foundered, the False Claims Act has become the most successful anti-fraud act in the United States.

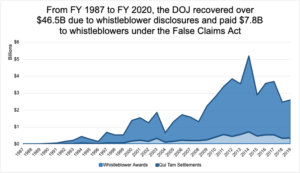

Compared to the six FIRREA settlements since the law was enacted in 1990, the DOJ has recorded at least 13,797 cases in which the government intervened based on whistleblower False Claims Act reports in the same time period. According to the DOJ, in FY 2020 alone, the government recovered over $2.2 billion in FCA settlements and judgements. Over $1.6 billion of that can be attributed to whistleblower-initiated cases. As an additional testament to its success, 31 states have established state versions of the False Claims Act, showing that it is widely applicable and necessary across the United States.

NWC’s previous analysis also shows that even successful whistleblower-assisted FIRREA prosecutions resulted from the False Claims Act’s strong incentives. Edward O’Donnell, the former Countrywide Vice President, originally blew the whistle on widespread fraud at Countrywide by voluntarily provided original information under qui tam provisions of the False Claims Act. While the FCA charges were later removed, the DOJ proceeded on FIRREA charges and the parties reached a $1.27 billion dollar settlement, with $57 million set aside for the whistleblower reward.

Public Support for Strengthening FIRREA

Corporate whistleblowers enjoy broad public support. A Whistleblower News Network poll released in October 2020 shows that the American public considers corporate fraud a national priority and wants to help whistleblowers who expose it.

A key way to do so would be to strengthen FIRREA, a fact that has been highlighted by government officials as well as whistleblower advocates.

In 2014, Attorney General Eric Holder, on behalf of the DOJ, called for FIRREA’s whistleblower reward provision to be reformed. He argued that lifting the caps on whistleblower rewards “could significantly improve the Justice Department’s ability to gather evidence of wrongdoing while complex financial crimes are still in progress – making it easier to complete investigations and to stop misconduct before it becomes so widespread that it foments the next crisis.”

Stephen M. Kohn, NWC’s Board Chairman, has joined in these calls for reform, stating that “FIRREA is an older law that contains one of the worst federal whistleblower reward statutes…Ultimately, in order to promote the detection and prosecution of bank fraud, the FIRREA whistleblower provision will need to be fixed.”

Additionally, past experience demonstrates that the public is opposed to whistleblower reward caps. This can be seen from strong public opposition to an SEC proposal in 2018 to cap SEC whistleblower rewards.

In 2018, the SEC proposed amendments that would have created a cap on rewards and established an unrealistic reporting procedure. Of the more than 3,500 comments posted on the SEC’s public comment page, 99% spoke out against these changes, with many of them highlighting the damage a cap would do for incentivizing high-impact whistleblowers. The National Whistleblower Center also filed a historic petition opposing the two changes, which included 102,595 signatures, breaking the record for comments on an SEC whistleblower program change.

Expanding whistleblower reward incentives to the banking industry will be crucial for protecting investors, taxpayers and the public interest. The billions collected in fines from similar programs show what FIRREA could be capable of if whistleblowers were incentivized to report violations in banking and finance. By lifting the cap on whistleblower rewards, Congress can meaningfully incentivize whistleblowers, proven to be the most effective source of information on fraud, to work with regulators to deter, detect and prosecute financial fraud.