The disruption of the earth’s climate is one of the greatest challenges facing our society. Greenhouse gas emissions are continuing to increase, as evidenced by a Global Carbon Project report finding that in 2019, despite impressive progress with clean energy, global fossil fuel emissions had increased for the third straight year. And these emissions are already having dramatic impacts.

Sea levels are rising. Animal and plant species are rapidly going extinct. Natural phenomena like hurricanes and forest fires are becoming increasingly more violent. And the impacts of greenhouse gas emissions are not spread evenly. Those who have contributed the least to the problem – the poorest communities around the world and the generations to come – will experience the greatest impacts.

Climate change poses an enormous threat to our economy and quality of life, and readily available solutions are not being implemented fast enough to head off the worst damage. That’s why the National Whistleblower Center (NWC) launched our Climate Corruption Campaign in January 2020, with a focus on the fossil fuel and timber industries as well as their professional enablers, including the securities and banking industries.

The Climate Corruption Campaign’s securities work is focused on one central concept: major corporations and large financial institutions are significantly exposed to climate risks, and these institutions are not moving toward net-zero financing at the pace or scale necessary to avoid destabilizing the climate or the economy.

Without sufficient disclosure requirements and oversight, corporations or financial institutions could hide the extent of their climate-related financial risks or make misleading claims about their sustainability efforts. That’s why NWC is calling on financial regulators to create thorough, robust and mandatory climate-related disclosure requirements for companies and financial institutions.

However, while stronger disclosure requirements are necessary to protect the environment and the economy, whistleblowers don’t have to wait. Whistleblowers can currently use powerful U.S. whistleblower laws to report climate-related financial fraud, including the failure to disclose material climate-related risks. NWC is educating and assisting whistleblowers in the fossil fuel, timber, and enabling industries with evidence of climate-related risks and other potentially fraudulent information. Learn more about how we help whistleblowers find an attorney here.

REPORT CLIMATE CRIMES CONFIDENTIALLY

Stronger Disclosure Requirements are Needed

Regulators, politicians and market participants are beginning to recognize the serious and systemic risk that climate change poses to financial stability and the need for mandatory climate risk disclosure regimes. Deception on climate-related risks could create what Mark Carney, the former Governor of the Bank of England, called a “Minsky moment,” a sudden collapse in the value of assets, resulting in a financial crisis.

U.S. whistleblower laws can be a powerful tool for stopping climate-related deception. Both whistleblowers and financial regulators have key roles in exposing financial fraud that results from the failure to disclose climate risk. The Dodd-Frank Act legislated some of the most powerful whistleblower protections in the world, establishing an extremely successful whistleblower office at the SEC for securities whistleblowers as well as strengthening protections for commodities and foreign bribery whistleblowers around the world.

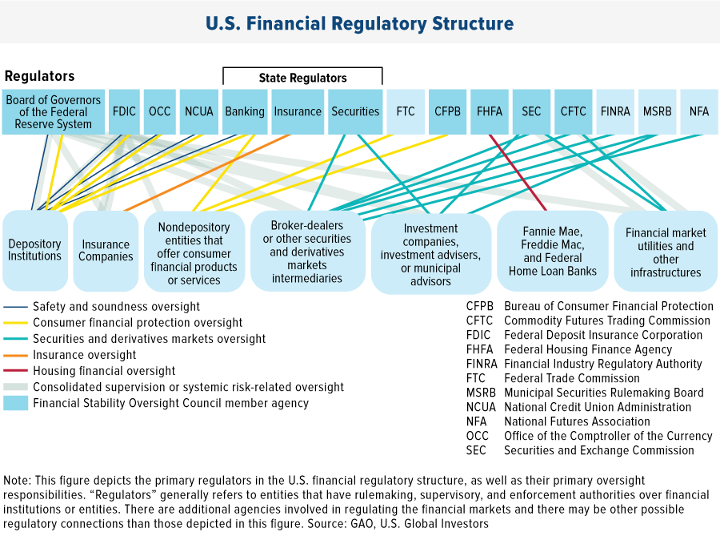

However, for the Dodd-Frank Act to work, it must be supported by disclosure requirements that adequately account for climate risks. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has the authority to require standardized corporate climate disclosures for publicly-listed corporations, including publicly-listed bank and nonbank financial institutions.

Numerous voluntary initiatives now exist to encourage greater corporate disclosure of climate-related risks, including the CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) and the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TFCD). However, companies and financial institutions have a strong financial incentive to stay on the same path and to value short-term profits over long-term risk management. They are unlikely to make necessary adjustments on their own.

For disclosures to be effective, a report from the Climate Risk Disclosure Lab highlights that there must be a thorough, robust and mandatory disclosure framework for climate-related information. As SEC Commissioner Allison Herren Lee commented, “[I]t is … clear that the broad, principles-based “materiality” standard has not produced sufficient disclosure to ensure that investors are getting the information they need – that is, disclosures that are consistent, reliable, and comparable.”

NWC is working closely with partners at Duke University in a project called the Climate Risk Disclosure Lab to facilitate the development of these rules and to ensure that they are harmonized with rules being developed by securities regulators outside the U.S.

With stronger disclosure requirements mandated by agencies and lawmakers, whistleblowers can better assist financial regulators in identifying otherwise hidden risks that could threaten the environment and the economy. While many investors are currently in the dark on climate risks, company insiders may know the extent to which the impact of climate change-related risks on financial assets have been illegally concealed from investors, regulators, and the public.

These actions can be further supported by integrating climate risk into financial institution oversight for the banking industry. Learn more about NWC’s related work to strengthen oversight in the banking industry here.

How to Strengthen the U.S. Securities Disclosure Regime

Mark Carney has called for rules to be enacted by countries around the world to ensure that climate risk disclosures are comprehensive and comparable. The U.S. SEC has signaled that it will follow this approach by reviewing and updating its guidance on climate-related risk disclosures.

On February 24, 2021 Acting Chair Allison Herren Lee directed the Division of Corporation Finance to review the effect of the agency’s previous 2010 guidance on climate-related disclosures. The 2010 guidance reminded issuers that they must disclose climate-related risks if they are material but did not require issuers to disclose specific climate-related information. The Division of Corporation Finance will now engage with companies and assess how the market is currently managing climate risks in order to begin updating the 2010 guidance. Notably, the SEC emphasized that it would be relying on whistleblowers in identifying material gaps and misstatements in these disclosures.

In a statement, Herren Lee explained “Ensuring compliance with the rules on the books and updating existing guidance are immediate steps the agency can take on the path to developing a more comprehensive framework that produces consistent, comparable, and reliable climate-related disclosures.”

On March 15th, the SEC announced a 90-day public comment period, requesting information from investors, registrants, and other market participants on climate change disclosure.

The SEC could require standardized corporate climate disclosures and provide specific direction regarding fossil fuel accounting and auditing. The Climate Risk Disclosure Act, introduced by Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Sean Casten in the 116th Congress, models what the SEC could require companies to disclose, including direct and indirect greenhouse emissions, fossil fuel assets, their climate risks, and plans to mitigate those risks.

It is important to note that an effective disclosure regime would need to apply to not just to fossil fuel and deforestation-linked companies, but also to the banks and nonbank financial institutions that finance and invest in these companies. A recent report from the Center for American Progress highlights that the SEC can prioritize the financed emissions of the financial sector and has the authority to “achieve as close as possible to a federal mandate for disclosure of financed emissions.”

The SEC can require disclosures from any publicly-listed corporation, including publicly-listed banks and publicly-listed nonbank financial institutions, such as asset managers, bank holding companies, and insurance companies. This would include the top banks fueling climate change, such as JP Morgan, Citigroup, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo, as well as the bank holding companies that own and control them. In addition to publicly-listed corporations, the SEC can also require disclosures from other securities market participants such as stock exchanges, securities brokerages, mutual funds, auditors, and investment advisors.

The Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) can also address climate risks in the commodities and derivatives markets. As the Revolving Door Project has highlighted, the CFTC requires swap dealers in these markets to disclose certain risks and could require them to disclose climate-related risks as well. The CFTC could also incorporate climate risk into stress tests for derivatives clearinghouses and require market participants to hold adequate capital for managing climate risks.

NWC is working with other transparency groups to advocate for stronger climate risk disclosure requirements. Stronger disclosure requirements and greater oversight of climate risks could ensure that market participants have a transparent understanding of new risks.

Strengthening Oil, Gas, and Mining Payment Disclosures in the U.S.

Improving risk disclosures for oil and gas and mining companies will also require strengthening Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Often referred to as the Cardin-Lugar amendment, Section 1504 deals with disclosures of payments to foreign governments for oil, gas or minerals, which function as bribes in the opinion of anti-corruption experts, yet often slip through loopholes in laws like the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

The Cardin-Lugar amendment directed the SEC to issue a rule requiring companies to detail their payments in annual reports posted on the SEC website along with other public filings. However, the U.S. oil and gas industry has aggressively fought the development of this rule, claiming that disclosures would put them at a competitive disadvantage and would jeopardize operations in countries that prohibit public financial disclosures. These arguments have derailed multiple attempts to implement the amendment.

The latest rule, unveiled in December 2019, redefines every standard of disclosure, allowing companies to report only the broadest level of engagement with foreign governments, while adding new exemptions and loopholes that will allow some companies to avoid disclosures altogether. While the SEC voted in favor of the rule in December 2020, industry lobbying has so weakened the rule that, in its current form, it will not shed any light on financial activity for investors.

The National Whistleblower Center is working with anti-corruption allies to reverse this ruling. To develop a stronger rule, the U.S. can look to similar laws in the European Union and Canada. These laws have more stringent requirements than even the SEC’s original rule. Several years after their implementation, they have compelled disclosures from hundreds of companies.