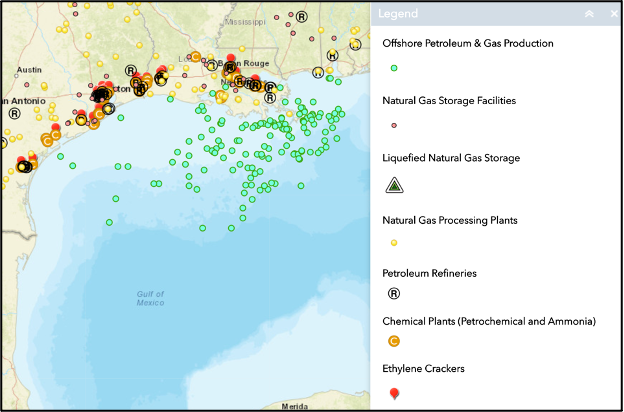

The Gulf of Mexico is a crucial area for U.S. oil and gas resources and infrastructure. The region is the technical and financial center of the oil and gas industry, with many company headquarters concentrated along the Gulf Coast. This region is home to one-fifth of total crude oil production in the U.S., 45% of U.S. petroleum refining capacity and 51% of U.S. natural gas processing plant capacity. The Gulf Coast is also an important petrochemical hub, representing more than half of U.S. downstream chemical production, with at least fifty-five major chemical plants.

- Fractracker Alliance, “National Energy and Petrochemical Map.”

Since 2012, the Gulf has seen a construction boom of offshore oil and gas infrastructure, refineries, LNG terminals, ethylene cracker plants, and chemical and fertilizer plants. According to the Environmental Integrity Project, since 2012, Texas and Louisiana have approved Clean Air Act permits for at least 74 oil and gas and petrochemical projects within 70 miles of the Gulf Coast shoreline.

The oil and gas industry increasingly faces new risks created by climate change. Without credible plans for a transition to a lower-carbon business or even realistic emissions targets, many oil and gas companies operating in the region remain unprepared for the energy transition. If companies do not prepare quickly, executives will increasingly face pressure to cover for struggling performance or bad investment choices in expensive reserves, raising the risk of fraud.

If you need help or want to contact an attorney, please fill out a confidential intake form. To learn more about how NWC assists whistleblowers, please visit our Find an Attorney page.

Climate change creates new threats to oil and gas infrastructure

Oil and gas infrastructure in this region will be particularly affected by transition risks – market changes that will occur as the world transitions to adapt to climate change. As the world transitions to low-carbon energy sources, Carbon Tracker has predicted that a significant portion of oil and gas reserves will become too costly to extract, turning them into “stranded assets.” Because they are unusually complex and costly, deep water assets in the Gulf of Mexico are among the assets most at risk of becoming stranded.

In addition to these transition-related risks, the oil and gas industry will face climate-related physical risks. Offshore production in the Gulf of Mexico is more exposed to extreme weather than other areas around the world. Research from Verisk Maplecroft, which measures asset-level company and industry exposure to ESG risks, found that, in 2017, 72% of U.S. offshore production, most of it in the Gulf of Mexico, took place in areas designated as “high” or “extreme” risk, compared to 7% worldwide.

Refineries and petrochemical plants in the region, which are built predominantly in low-lying coastal areas, also face a high risk of flooding. A June 2020 report from Jupiter Intelligence highlighted the physical risks facing petrochemical facilities near Houston. Examining three vulnerable facilities, the report estimated that the flooding area of the three facilitates will double by 80% in the next ten years and that damage to property and equipment from extreme flood events will rise by 3-8 times.

As climate change increases the frequency and intensity of hurricanes in the Gulf, companies that fail to prepare will face a greater risk of infrastructure damage. With little oversight regarding how companies are preparing or how much they are disclosing about physical risks, there is also a higher risk that companies will be tempted to mislead investors about the risks and their preparation.

As pressure grows, companies could be tempted to hide environmental liabilities

Oil and gas drilling and transport poses a significant threat to the environment, one that has regularly been understated by the industry. Fraudulent attempts by companies to hide environmental damage or poor emergency preparedness can make this threat much more severe. In the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon disaster, an investigation by the Associated Press found that, in obtaining a lease, BP had vastly overstated its preparedness to deal with a major leak, while understating the dangers that a spill would pose to local environmental and public health. BP ultimately settled the allegation that it had violated the “reverse false claims” provision of the False Claims Act by lying on the leasing application as part of a larger settlement that totaled more than USD14 billion dollars. BP was also forced to pay USD525 million to the SEC for making fraudulent public statements about the extent of oil spilled in the aftermath.

Ten years after Deepwater Horizon, oil spills and accidents in the Gulf of Mexico are on the rise. Long-term financial challenges and the short-term crisis of the Covid-19 pandemic could also increase environmental and safety risks for offshore drilling. Financially challenged companies may be tempted to cut corners on safety, and the downturn in the oil and gas industry has led to major layoffs. A lack of trained workers can reduce a companies’ emergency preparedness. After Shell’s “Jumper” pipeline leak in 2016, a Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement report found that after the company’s previous layoffs, there were not enough experienced and trained employees to identify the risks, leading to a slower response.

Additionally, climate change could add new pressure on environmental liabilities related to retiring long-lived oil and gas infrastructure. Asset retirement obligations require companies to pay to plug and abandon wells at the end of their life in accordance with environmental standards. According to Carbon Tracker, as demand for fossil fuels falls below the projections that justified the development of wells, companies will need to accelerate the date of the wells’ retirement. Many companies have delayed abandonment as long as possible and may not have saved enough money to pay for reclamation, creating the potential for “stranded liabilities.” As pressure grows, companies could be tempted to falsely represent wells as “idled” rather than “abandoned” or to understate the expected cost of asset retirement obligations to investors.

With new challenges, the motivation for reserve overstatement fraud could rise

Climate-related challenges and financial pressure could add additional motivation for fraud related to oil and gas reserve estimates. As an already subjective estimate, reserve valuations are particularly ripe for misrepresentation. The technical and complex nature of reserve estimates makes it difficult for auditors inexperienced in reservoir engineering to evaluate the accuracy of company reports, and auditors have a poor track record of catching even the most notable overstatements.

With growing pressure on companies and few external checks, the pressure to withhold negative developments concerning key discoveries in the Gulf of Mexico could be high. An ongoing case brought forward by a whistleblower highlights how executives might manipulate information to delay disclosing negative news regarding reserves.

In 2016, whistleblower Lea Frye, a former senior reservoir engineer at Anadarko, filed a complaint with the SEC alleging investor fraud and insider trading at Anadarko related to the company’s Shenandoah field in the Gulf of Mexico. The complaint accused executives at Anadarko of misleading investors and Occidental Petroleum, which purchased Anadarko in 2019, by fraudulently inflating the value of the Shenandoah field by millions or even billions of dollars.

According to documents unsealed in August 2020, Frye alleged that the company rejected and hid internal drilling reports that consistently showed the Shenandoah field had far less oil than previously predicted. By inflating the value of the reserves, executives were able to misrepresent the value of the company before selling to Occidental Petroleum for $38 billion and to receive hundreds of millions in golden parachute bonuses.

How whistleblowers can help

Whistleblowers have already been instrumental to uncovering fraud related to offshore oil and gas in the Gulf of Mexico. In 1996, using the qui tam provision of the False Claims Act, a group of whistleblowers revealed a massive conspiracy by more than a dozen oil and gas companies to systematically defraud the government by underpaying royalties owed from leases in the Gulf of Mexico. After the Department of Justice joined the whistleblowers’ suit, the companies paid almost half a billion dollars to settled allegations that they had violated the False Claims Act. The whistleblowers received a total of more than USD45 million dollars in rewards.

Whistleblowers can use the Dodd-Frank SEC whistleblower program to confidentially report companies who are misleading investors about transition or physical climate risks, about the extent of environmental liabilities, or about the value of reserves. Whistleblowers can also the False Claims Act to report companies who make fraudulent statements to obtain a lease, such as understating their emergency preparedness.

Under the Dodd-Frank Act, whistleblowers who provide original information that leads to successful prosecution can receive between 10% and 30% of monetary sanctions. Under the False Claims Act, whistleblowers are eligible for 15% to 30% of the monetary sanctions. With growing pressure and financial challenges increasing the motivation for fraud, whistleblowers could play a crucial role in revealing fraud, while using these laws to protect their identities and qualify for a substantial financial reward.

To read about these whistleblower laws in more depth, read The New Whistleblower’s Handbook, the first-ever guide to whistleblowing. The Handbook, authored by the nation’s leading whistleblower attorney, is a step-by-step guide to the essential tools for successfully blowing the whistle, qualifying for financial rewards, and protecting yourself.