Around the world, as much as 23% to 30% of hardwood lumber and plywood traded globally could be from illegal logging activities. According to Interpol, illegal logging accounts for 50-90% of the total volume for all forestry tropical basins in Amazon Basin, Central Africa, and South Asia that are the key to regulating the climate. The high rate of illegal logging is driven by several factors that create a high risk of fraud, bribery, and other forms of corruption in the global timber trade.

To predict the conditions that lead to a high risk of fraud, anti-fraud professionals frequently rely on a concept called the “fraud triangle,” a model for understanding three conditions that lead to fraud:

- Motivation

- Opportunity; and

- The ability to rationalize fraud.

To identify industries that face a particularly high risk overall, researchers look for the widespread presence of these three factors.

When applying the “fraud triangle” to timber, the substantial profits created by illegal logging provide a strong motivation to engage in fraud and bribery. A 2017 report by Global Financial Integrity found that illegal logging is the most profitable natural resource crime, and Interpol estimates that forestry-related financial crimes generate between $51 and $152 billion per year.

Timber trafficking is often connected with other illegal trades, such as drug trafficking in cocaine-producing countries, and it can also provide a lucrative method for clearing land for agriculture or mining. Accepting bribes to turn a blind eye to forestry-related crimes can also provide a supplemental source of income for low-paid forest rangers, creating motivation among those who might otherwise protect forests to instead help facilitate timber theft.

Weak Enforcement and Corruption Enable Illegal Logging

While there are a growing number of laws designed to curb deforestation, a lack of sufficient law enforcement capacity undermines progress. Currently, many of the rules and laws designed to curb the illegal timber trade are either not strict enough or are poorly enforced. In 2018, an assessment by Chatham House and Climate Focus examined nine countries home to almost half of tropical forests. Their assessment found that while these countries had made progress in strengthening their laws over the previous five-year period, inconsistencies in the laws and lax enforcement led to major gaps.

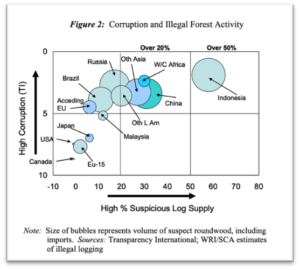

Corruption also undermines enforcement and creates opportunities for illegal logging throughout the supply chain. Several studies have found a strong correlation between deforestation levels and perceptions of corruption.

- Seneca Creek Associates and Wood Resources International, LLC “Illegal Logging and Global Wood Markets” (2004)

A 2016 Interpol report estimated the annual global cost of corruption in the forestry sector at $29 billion. Surveying thirteen countries, the report found an average of 250 identified cases of corruption in the forestry sector, while noting that most are likely not identified. The report identified bribery as the most common form of corruption in the global forestry sector, with government forest officials as the most common recipients of bribes and the harvest as the most common point of bribery.

Analysis from Forest Trends finds that many of the countries that export a significant amount of valuable timber are also identified as fragile or conflict-affected. In countries experiencing or emerging from armed conflict, the threat posed by bribery and weak law enforcement can be exacerbated. Revenues from forest resources can finance and fuel conflict, and the presence of armed conflict can increase opportunities for fraud and corruption.

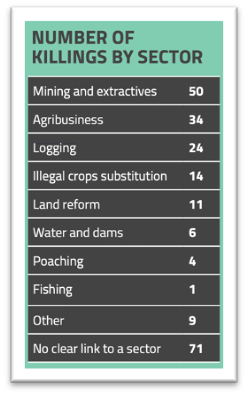

In countries struggling with corruption or armed conflict, illegal logging can also go undetected due to violent threats against environmental defenders. Global Witness’s annual report on the killings of land and environmental defenders in 2019 shows that 212 defenders were killed, the highest number recorded yet. Logging was the sector with the third highest number of killings, behind agriculture and mining. The logging sector had the highest increase in killings globally since 2018, with 24 defenders killed in 2019.

- Global Witness, “Defending Tomorrow” (2020)

Challenges in Detecting Timber Fraud

A wide range of factors also create unusual opportunities for illegal logging to flourish in countries with weak enforcement. The remote nature of large forests can make it difficult to monitor forests for logging. The illegal logging industry can also be intertwined with legal logging, making it difficult to isolate and identify illegal logging.

To evade regulations in countries with strong enforcement, traffickers can obscure the origins of the timber by sending it through countries like that have fewer regulations. A 2019 report by the nonprofit Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) found that trafficking of wood through China allowed timber illegally harvested from Africa’s Congo Basin to end up in furniture and flooring stores throughout America and Europe.

While laboratory forensic testing has improved, it remains difficult to employ at a meaningful scale. A study published in Plos One used forensic wood anatomy to test 183 specimens from 73 consumer products from major U.S. retailers. The results showed that more than 60% of the sample had misrepresented or fraudulent species labels. However, the report also found that the U.S. does not have the capacity for the kind of large-scale forensic testing that would be required to meaningfully deter timber fraud.

Rationalizations for Timber Fraud

The scale of illegal logging suggests that the ability to rationalize fraud and corruption is widespread. Participants in the illegal harvesting of timber are often encouraged to participate due to exploitative local economies and the threat of violence. Traffickers may rationalize participation based on the perception that “everyone” is engaged in the illegal trade or that importers know or should know about the illegality.

Two recent scandals in the timber industry also highlight that large, global importers can rationalize engaging in fraud. In 2012 Gibson Guitar Corp. entered into a criminal enforcement agreement with the Department of Justice to resolve an investigation into allegations regarding the purchasing and importing of ebony wood from Madagascar and rosewood and ebony from India. According to the Department of Justice, a Gibson employee had known that the wood would be illegally exported and warned superiors, but the company had continued to import it in violation of the Lacey Act.

In 2015, Lumber Liquidators was fined over $13 million in the largest Lacey Act fine to date for buying wood that had been illegally logged in eastern Russian forests. In describing the fine, former Assistant Attorney General John C. Cruden for the Justice Department’s Environmental stated, “Lumber Liquidators knew it had a duty to follow the law, and instead it flouted the letter and spirit of the Lacey Act, ignoring its own red flags that its products likely came from illegally harvested timber, all at the expense of law abiding competitors.”

How Whistleblowers Can Stop Timber Fraud

Substantial profits from illegal logging provide a strong motivation to engage in timber fraud, while loopholes, lax enforcement, and corruption provide extensive opportunities for fraud to go undetected. Cases against major timber importers show that the ability to rationalize fraud is not an isolated phenomenon, but one that is present throughout the supply chain.

Whistleblowers could play a powerful role in detecting and prosecuting timber fraud. A robust framework of U.S. whistleblower reward laws exist that can be used by whistleblowers to report instances of fraudulent activities within the illegal timber trade supply chain. These laws include the False Claims Act (FCA), Dodd-Frank Act, and the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA).

The False Claims Act is one of the most powerful whistleblower laws. Using the False Claims Act, whistleblowers can report “reverse false claims” violations, instances in which a wrongdoer has prevented the government from collecting what it is owed, such as customs violations. Under the False Claims Act, whistleblowers are eligible for 15% to 30% of the monetary sanctions. These rewards are often substantial, since under the False Claims Act, the criminal is liable for a civil penalty as well as treble damages.

Additionally, whistleblowers can use environmental laws with whistleblower provisions such as the Lacey Act or the Endangered Species Act. The Lacey Act has long been one of the most powerful U.S. laws for fighting wildlife trafficking, and a 2008 amendment to the Lacey Act banned the importing, exporting, buying, and selling of illegally sourced plants. The amendment also requires companies trading in most wood products to submit formal declarations of the species and origin of harvest. Whistleblowers who disclose original information that results in successful Lacey Act enforcement actions are eligible for a monetary reward.

With substantial challenges for law enforcement around the world, whistleblowers are needed to protect forests by helping to detect and prosecute companies and individuals that engage in forest fraud and corruption. Thanks to these powerful U.S. whistleblower laws, whistleblowers around the world are well-suited to detect and help prosecute timber fraud, while protecting their identity and qualifying for a reward.