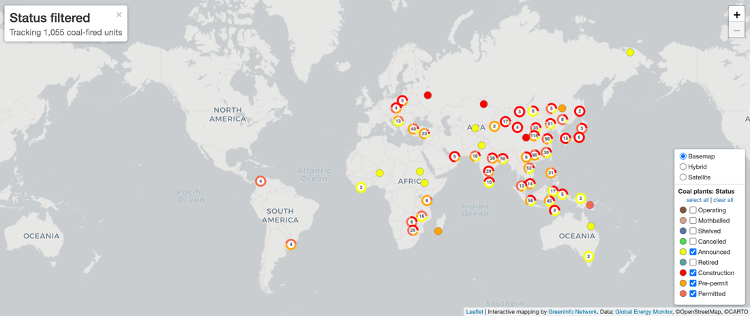

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the coal industry accounted for almost 40% of electricity generation and more than 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions in 2019. Even as the coal industry struggles in the United States and Europe, it remains powerful globally, and, while the pandemic drove a drop in coal demand in 2020, IEA forecasts a rebound for coal demand in 2021 led by China, India, and Southeast Asia. Figures from Global Coal Plant Tracker show that in 2020, 189.8GW of coal power capacity is under construction and 331.9GW is in planning.

The coal industry also continues to receive support from major financial institutions; the 2020 Banking on Climate Change report identified at least USD 54 billion in financing for coal mining and at least USD 38 billion in financing for coal power.

Growing concern, however, about coal’s climate impacts and competition from renewable energy has put tremendous pressure on the industry to prove that it can remain a major player long-term. As coal-fired power plants close and major financiers and insurers begin to back away, experts have begun to predict the ‘beginning of the end’ for the coal industry, suggesting that, while the industry remains powerful, it will face greater financial pressure moving forward.

To predict the conditions that lead to a high risk of fraud, anti-fraud professionals and researchers frequently rely on a concept called the “fraud triangle,” a model for understanding three conditions that lead to fraud: opportunity, motivation (which can take the form of incentives or pressure), and the ability to rationalize fraud. A combination of growing pressure to meet impossible financial expectations, a lack of effective oversight and scrutiny, and a history of rationalizing industry-wide deception, suggests that, as major players in the coal industry become desperate to extend the life of the coal industry, the industry is at a high risk for financial fraud. As the risk of financial fraud grows, coal whistleblowers could play an essential role in detecting and prosecuting fraudulent schemes.

A map from Global Coal Plant Tracker shows future coal buildout, with 1,055 coal-fired units that have been announced, are either pre-permit or permitted, or are currently under construction.

The risk of securities fraud

When companies face financial pressure, the potential for fraudulent behavior is particularly acute. The risk of fraud is high where finance, production, sales and operations managers face pressure to deliver positive results, and companies allow internal controls to erode. Data from a recent EY survey shows that, in the oil, gas and mining industry, 42% of employees would engage in fraud to meet financial targets and 36% would engage in fraud to help a business survive a downturn. As the coal industry faces growing regulatory and financial threats to the core of its business model, the pressure to meet targets and prove the industry’s long-term viability may tempt some to engage in securities fraud.

In 2012, a financial scandal at Rio Tinto revealed how executives under pressure could allow a fear of revealing negative news to snowball into billion-dollar fraud. Facing significant pressure to prove that the company could rebound from the high-profile failure of a recent acquisition, executives at Rio Tinto hid data showing that deposits in a new, highly publicized coal project in Mozambique contained only half as much coal as originally estimated and that the coal was less valuable than originally thought. While the USD 3 billion-dollar fraud was ultimately uncovered, the company wrote down the value of the project only after raising USD5 billion in U.S. debt offerings that contained misleading statements and omissions.

Allegations from a former employee at Australian coal mining company TerraCom suggest that similar fraudulent schemes concerning the quality of coal could be taking place today. In 2020, a former general manager at TerraCom alleged that TerraCom had pressured coal inspectors at inspection giant ALS to fraudulently improve coal analysis results. According to the Australian Financial Review, ALS conducted an internal investigation and informed the Queensland fraud police that between 45% and 50% of coal export certificates were “manually amended without justification” between 2007 and 2020. By altering the certificates, the lab employees and clients were able to exaggerate the amount of energy that the coal would give off, improving its value, while also potentially understating its environmental impact.

In addition to overstating the value of their coal, some companies could attempt to mislead investors and the government about the extent of their liabilities. Companies could attempt to shed liabilities by selling assets to smaller, underfunded companies destined for bankruptcy or fraudulently understate the liabilities in their own bankruptcy process. A 2019 study of U.S. coal companies published in the Stanford Law Review found that, between 2012 and 2017, four of the largest coal companies in the U.S. managed to evade USD5.2 billion of environmental and retiree liabilities through bankruptcy filings.

False promises about the potential of “clean coal” technologies have also proved not only generally misleading but conducive to financial fraud. Promising viable clean coal technology, the CEO of Bixby Energy was able to raise USD 57 million from investors before it became known that the technology had never worked. In another case from 2016, a whistleblower revealed that Southern Company had been lying about the cost and timeline of its flagship “clean coal” Kemper Project, which had received hundreds of millions of dollars from the U.S. federal government. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Justice opened an investigation after the company wrote off USD 6.4 billion in costs related to the project.

Greater pressure to engage in bribery

As the coal industry faces growing financial challenges that have only intensified due to the outbreak of coronavirus, companies could become desperate to obtain or retain permits or contracts or to avoid regulations. Coal mining companies have previously engaged in corrupt practices to gain influences with public officials. In 2015, the SEC charged BHP with violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act related to its sponsorship of foreign government officials at the Beijing Summer Olympics. BHP had invited 176 government officials and employees of state-owned enterprises from around the world to attend the Games at the company’s expense, including government officials connected to pending contract negotiations or regulatory dealings, such as the company’s efforts to obtain access rights.

As coal mining and coal power companies face increasing competition from more cost-effective renewable energy, some executives may be tempted to protect investments in coal mines or plants by bribing politicians or regulators. In 2020, an whistleblower, Michael Pircio, helped launch an investigation into the utility company FirstEnergy. In a criminal complaint filed on July 21, 2020, federal investigators alleged that FirstEnergy paid USD 60 million to Generation Now, a fund controlled by then Ohio-Speaker Larry Householder, in exchange for providing a USD1.3 billion bailout for FirstEnergy’s struggling coal and nuclear plants. The complaint alleges that Householder used the money to build his political power, pass a bailout benefiting FirstEnergy’s coal and nuclear plants and then defend it from a ballot measure. The Securities and Exchange Commission launched an investigation into FirstEnergy in September 2020.

Bribery could also allow companies to hide evidence of securities fraud. The TerraCom whistleblower alleges that bribery enabled the Australian coal grading scandal. The altered inspection certificates at the center of the scandal should have been identified through the use of multiple inspection periods, on board, in port, and at the final destination. However, according to the whistleblower, TerraCom and commodities giant Noble bribed Chinese officials and select employees of South Korean state-owned enterprises to ensure that customers did not complain about the analysis manipulation.

The risk of climate risk disclosure fraud

The financial impacts of climate change have also drawn particular attention to the potential for securities fraud related to disclosures on the potential impacts of climate change and environmental regulations. Coal has the largest carbon footprint of any fossil fuel, and has historically been the “single biggest contributor” to climate change. The coal industry’s assets are particularly at risk from the so-called carbon bubble.

Investor groups have been warning for years that current SEC disclosures related to climate risk are insufficient. Under the current framework, companies essentially decide for themselves whether a particular climate change risk is sufficiently material to investors to be disclosed and, if it is, how it must be disclosed. Without thorough climate risk disclosure requirements, investors are left without sufficient details on how companies are preparing for the energy transition.

A series of previous settlements highlight the potential for misleading disclosures. In 2007, under New York state’s Martin Act, the New York Attorney General subpoenaed the executives of five energy companies with major coal assets, including Peabody Energy, at the time the world’s largest coal company. The investigation into Peabody’s disclosures found that the company had violated the Martin Act by misrepresenting demand for coal to investors and failing to disclose to investors internal projections about potential liabilities related to climate change. Peabody, along with the four other companies, Xcel, Dominion, Dynegy, and AES Corporation, settled by entering into an agreement that required the companies to provide more information regarding material risks related to climate change.

However, the industry’s decades-long dependence on deception and denial about climate science suggest that future disclosures about climate risks will continue to deserve close scrutiny. The coal industry was one of the earliest groups to know about the science of climate change, with records suggesting the industry knew more than fifty years ago. Yet, rather than communicating the risks, the industry became one of the earliest funders of climate change denial campaigns designed to stymie regulations. It has continued to be a major funder today. As major American coal companies have gone bankrupt, the bankruptcy filings of several major coal companies have revealed that even as they struggled financially, they continued to quietly fund think tanks focused on climate change denial.

In July 2020, NWC released a report detailing widespread deception by fossil fuel executives regarding the financial risks of climate change. The report, entitled Exposing a Ticking Time Bomb: How Fossil Fuel Industry Fraud is Setting Us Up for a Financial Implosion – and What Whistleblowers Can Do About It, calls for collaborative investigations by whistleblowers and law enforcement authorities of likely securities fraud violations.

It found that deception about the financial risks of climate change is pervasive across the fossil fuel industry, with two categories of material information routinely omitted from companies’ statements to shareholders: (1) the immediate risks that climate change poses to companies’ financial condition, and (2) the risk that the company’s asset deflation will contribute to an economy -wide financial implosion.

- Exposing a Ticking Time Bomb

- Key Findings

- Recommendations