Foreign Corrupt Practices Act: How the Whistleblower Reward Provisions Have Worked

Published August 2018

Download the PDF version of the report with reference section here.

Part 1

Point A: Whistleblower Reward Laws for FCPA

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act permits rewards to whistleblowers who provide original information about bribes paid to foreign government officials by publicly-traded companies or U.S. persons.

Whistleblowers are entitled to a financial reward between 10% and 30% of all sanctions obtained by the U.S. government. These rewards are available to non-U.S. citizens, for bribes paid outside the United States. The whistleblower claims can be filed anonymously and confidentially.

The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”) is one of the most important anti-corruption laws. Originally passed in 1977, the FCPA prohibits companies issuing stock in the U.S. (including non-U.S. companies that trade in American Depositary Receipts, “ADRs”, which allow for U.S. investors), and their subsidiaries, from bribing foreign officials for government contracts or to obtain any business advantage.

Bribery includes paying, promising or offering to pay, or authorizing the payment of money or anything of value to a foreign official, international organization official, political party, party official, or candidate for public office, with the intent to wrongfully induce the recipient to misuse his or her official position or to secure any other improper advantage in order to obtain or retain business. These same provisions apply to bribes made through third-parties if made with the knowledge that all or part of the bribe will be offered, given, or promised, directly or indirectly, to a foreign official. Foreign nationals and foreign, non-issuer companies may also be held accountable under the FCPA for aiding and abetting and FCPA violations or for conspiring to violate the FCPA.

The inclusion of parent company liability for actions by subsidiaries is a significant advantage to the efficacy of the FCPA. This ensures that even extremely large or diffuse companies internally enforce compliance protocols, a key step in corruption prevention.

The FCPA also mandates strict record keeping requirements. This is because the law recognizes that people use accounting and financial gimmicks to hide violations of the law. Sanctions for violations of bookkeeping requirements are in many cases larger than sanctions for paying bribes.

The law does something that the average layperson may think is not possible: the FCPA establishes U.S. jurisdiction for bribes paid in foreign countries by foreign nationals to foreign government officials. This means that the FCPA is applicable even if bribes are paid in a foreign country and the whistleblower is a foreign national, which gives it international reach in a particularly effective way.

FCPA establishes U.S. jurisdiction for bribes paid in foreign countries by foreign nationals to foreign government officials.

Point B. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Jurisdiction

Enforcement of the FCPA falls under the jurisdiction of two law enforcement agencies: the U.S. Department of Justice (“DOJ”) and the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). The DOJ largely prosecutes criminal cases, while the SEC handles civil violations of the FCPA. However, the SEC does have the mandate to prosecute criminal cases, and does so in rare instances. The SEC is also the agency with jurisdiction to review and approve whistleblower rewards.

The SEC has acknowledged that whistleblower tips are “among the most powerful weapons in the law enforcement arsenal” to help the U.S. government identify violations “much earlier than might otherwise have been possible,” thus “more swiftly hold[ing] accountable those responsible.” The SEC has paid millions of dollars in rewards to foreign nationals.

Corruption is an insidious plague that has a wide range of corrosive effectives on societies. It undermines democracy and the rule of law, leads to violations of human rights, distorts markets, erodes quality of life, and allows organized crime, terrorism, and other threats to human security to flourish.

— Former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annnan, introduction to the U.N. Convention Against Corruption (2003)…

Point C: Blowing the Whistle Under the FCPA

FCPA whistleblower provisions are uniquely designed to protect non-U.S. citizens. The confidentiality provisions of the whistleblower law enable non-U.S. citizens to blow the whistle on bribery, while maximizing the potential that the corrupt officials, company, or otherwise will not learn their identity. Whistleblowers are compensated if their information results in a successful prosecution. They are paid directly by the United States government, and the company and/or officials they turned in may never even become aware that a whistleblower turned them in.

The procedure for filing an anonymous whistleblower claim under the FCPA is straightforward. First, as required by the SEC, the whistleblower must hire a U.S.-licensed attorney. Second, the whistleblower must provide the attorney with his or her original information and must sign an official form from the SEC known as a “TCR” (Tip, Complaint or Referral). Third, the signed TCR is provided to the attorney, who must keep it in their files. Fourth, the attorney redacts all of the whistleblowers identifying information, and signs the TCR verifying the filing under oath. The attorney then files the TCR directly with the SEC. Thus, although the U.S. government is not provided with the name of the whistleblower, the whistleblower’s attorney can be held accountable for any misconduct by the attorney or whistleblower.

If the anonymous whistleblower’s information results in a successful enforcement action in which the SEC obtains a sanction of $1 million or more, the whistleblower is entitled to a reward between 10% and 30% of all sanctions obtained. However, in order to obtain the reward, the whistleblower is required to inform the SEC of their identity and submit an application for award. This notification is necessary to ensure that the whistleblower is not a “disqualified” person, such as an employee of the SEC. The SEC is still required to keep the whistleblower’s identity strictly confidential, and all rewards are paid on a confidential basis.

Sanctions Under the FCPA:

- VimpelCom: $795 million

- GlaxoSmithKline: $20 million

- Och-Ziff: $412 million

- LAN Airlines: > $22 million

- Novartis AG: $25 million

- Alcalel-Lucent: $137 million

- BAE Systems: $400 million

- Hitachi: $19 million

Point D: It’s Proven: Whistleblowing Works!

Statements from elected leaders, law enforcement officials who work directly with whistleblowers on the ground, and appointed leadership in the agencies that implemented whistleblower programs demonstrate high regard for whistleblowers. Statistics on the use of whistleblower tips by the relevant agencies verify their effectiveness.

Whistleblower tips are by far the most used detection method for U.S. agencies. Additionally, reports released by the SEC Office of the Whistleblower on the use of whistleblower tips verify the effectiveness of these tips.

For example, approximately 15% of whistleblower tips received by the SEC lead to some form of investigation. By comparison, the DOJ has an intervention rate (including settlements) of nearly 25% in qui tam False Claims Act cases that are filed by whistleblowers. Further, in FY 2017, the U.S. government recovered over $3.7 billion through its civil fraud program. Of this amount, whistleblowers were directly responsible for the detection and reporting of over $3.4 billion (92%), under qui tam provisions. As a result of this assistance, whistleblowers were awarded $392 million (11.5%).

A strong monetary incentive to blow the whistle does motivate people with information to come forward… without the negative side effects often attributed to them.

— Alexander Dyke, et al., University of Chicago Booth School of Business

» Statements from elected and appointed leadership in the agencies that implement whistleblower programs.

» Statements from law enforcement officials who work directly with whistleblowers on the ground.

» Statistics on the use of whistleblower tips by the relevant agencies.

» Data on the amount of money collected by the government and distributed to whistleblowers after successful prosecutions and settlements that are only or largely possible because of whistleblower information.

Whistleblowers play an integral role in keeping institutions honest, ethical, and safe, providing information to both law enforcement for prosecutions and to civil society for accountability to the public.

[The] “whistleblower program . . . has rapidly become a tremendously effective force-multiplier, generating high quality tips, and in some cases virtual blueprints laying out an entire enterprise, directing us to the heart of the alleged fraud.”

— Former Chairman Mary Jo White, Securities and Exchange Commission, remarks at the Securities Enforcement Forum, Washington DC (2013)

Given the nature of fraud and corruption, it’s not surprising that the SEC and DOJ find whistleblower provisions a crucial part of the success of the FCPA.

E. Unwarranted Concerns

Many question whether financial rewards could incentivize set-ups, or the entrapment of otherwise-innocent or not-proven-guilty targets. Under this assumption, false tips accusing a target will result in charges against them. However, studies demonstrate that this is not the case in practice. Moreover, the system itself prevents these types of situations.

Whistleblower rewards have been demonstrated to incentivize high-quality tips to law enforcement. The amount of a reward stems from the amount of sanctions obtained after the successful conclusion of a case, and law enforcement will focus on tips for larger frauds and other illicit activities.

» A reward requires a successful prosecution by government officials, not just a tip.

» Law enforcement officials investigate the whistleblower’s information, just as they do in all civil or criminal cases. Whistleblowers may work within the investigators as ongoing sources of information, but must do so under the direction of law enforcement.

» Prosecutors can decline to charge in cases where the whistleblower has provided tainted evidence, or the information provided is not sufficient to justify filing charges.

» Cases which are not successful do not result in any sanctions or fines, and as such, no whistleblower reward. This incentivizes whistleblowers and their counsel to provide the strongest possible evidence, and discourages frivolous filings. » Finally, U.S. law may deny those who plan and initiate the crime from receiving whistleblower rewards.

» Finally, U.S. law may deny those who plan and initiate the crime from receiving whistleblower rewards.

There is demonstrable evidence that frivolous lawsuits are not a real concern. The University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business’ study debunked any allegations that the oldest and most successful whistleblower reward law, the False Claims Act, increases the filing frivolous litigation.

Congressional testimony by the U.S. Department of Justice confirms that qui tam lawsuits do not cause the government unnecessary litigation costs, but instead save it significant amounts of money by providing the DOJ with high-quality information necessary to investigate complex and secretive fraud.

Moreover, a Journal of Business Ethics study analyzed “the actual amounts of misused public funds recovered”. It found that “the actual benefits of the actual costs in the United States ranged from 14:1 to 52:1, the average being 33:1.”

This was confirmed by a comprehensive study commissioned by the European Union. The estimates from the Journal of Business Ethics study were used as a benchmark for the European Union study. The study noted that, “for the EU as a whole, the potential benefits of effective whistleblower protection are in the range of EUR 5.8 to 9.6 billion each year in the area of public procurement exclusively.”

[T]here is no evidence that having stronger monetary incentives to blow the whistle leads to more frivolous suits.

— Alexander Dyke, et al., University of Chicago Booth School of Business

F. How the National Whistleblower Center Supports FCPA Whistleblowers

The National Whistleblower Center (“NWC”) is a non-partisan, nonprofit organization that has worked for over thirty years to promote whistleblower rights and protections through a variety of avenues, including litigation, legislative advocacy, and public education. NWC’s expertise lies in its advocacy and litigation on behalf of whistleblowers, including through the use of impact litigation.

NWC focuses on altering the perception of whistleblowers and creating a culture of acceptance and appreciation through education and outreach, with a goal of ingraining the value of whistleblowers in society. Whistleblowers should be viewed not as informers (“rats”), but instead as productive and positive members of an active civil society, and as tools for good governance. Corporate culture should welcome whistleblowers as part a well-run internal compliance program to root out malfeasance.

National Whistleblower Center is a non-partisan, nonprofit organization working for whistleblowers for 30+ years.

NWC believes that effective law enforcement and community empowerment can both be furthered by a marketplace in which attorneys are incentivized to take such whistleblower cases, and where those with information are incentivized to become whistleblowers. To this end, NWC develops cases that can establish or utilize a working framework for further law enforcement action on corruption and bribery where whistleblower information is essential.

These cases will help develop a cycle of accountability through:

(1) detection by whistleblowers

(2) prosecution based on whistleblower disclosures

(3) sanctions which sponsor the continued detection of crime, deter future crime, and trigger self-enforcement

(4) use of the collected proceeds to benefit the public through restitution and rewards. As a result of the cycle of accountability, these laws can be self-funding and self-sustaining over time.

Fig 2 | The Cycle of Accountability

PART II:

Section A. Introducing the data

Much can be learned by looking at the court documents of FCPA prosecutions disseminated by both the SEC and the DOJ. Documents relating to FCPA prosecutions released by both the SEC and the DOJ provide valuable insights and data. The National Whistleblower Center has compiled data on all FCPA prosecutions from 1977, when the FCPA was originally passed by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Carter, through June 2018.23 This data includes 262 companies and 300 individuals.

For over four decades, the FCPA has been used to stamp out bribery around the world. How this has been done is crucial for the effectiveness of this law as well as future laws targeting this issue. In doing so, the data can function as an institutional understanding of the data also functions to increase the understanding of the use of whistleblower tips in the law enforcement process. While the information from court documents does not specifically include the role of a whistleblower in the case, what we do know about whistleblowers can inform the way that we analyze and interpret this data as well. Under the FCPA whistleblower provision, the whistleblower’s role must be kept strictly confidential, and has never been directly referenced in public decisions or even in the SEC’s reward rulings. Moreover, when prosecutions are based on information provided by confidential informants, the role of those informants is usually kept secret.

Section B. What we know, and what we don’t know, about this data

This data, sourced from the SEC and DOJ directly, is arguably the most complete set of data on this issue that is legally and practically possible for a group outside of the government to procure and publish.

As with any data set, there are limitations that must be addressed. The data is sourced directly from the SEC and DOJ websites that lists FCPA enforcement actions.24 For some cases, the data was taken directly from court document attachments, but for others, the data was gleaned from related press releases. This reflects the current chaotic nature of where and how this information is publicly available. Both websites were used to encompass the two enforcement agencies tasks with enforcing the FCPA. It must be noted, however, that while the DOJ and SEC prosecute violations of multiple laws, the scope of this data was exclusively FCPA prosecutions.

Note that prosecutions of individuals often involved multiple individuals, while the company cases would have only a single company. As are a result, NWC has maintained the data in distinct groupings, to ensure that the analysis of the data, as well as the lessons learned, remains both accurate and true. Additionally, this report has an emphasis on prosecutions against companies, rather than individuals, because of the important conclusions that can be drawn from market behavior.

Naturally, some information was incomplete and is reflected accordingly in the data set. Both the sanctions against companies and those against individuals contained some cases with incomplete data, the majority of which were against individuals. Incomplete cases were left off of the statistical and graph analyses, rather than coded as zeros. These analyses contained only the complete information as to not drastically decrease averages with inaccurate sanction values of zero. The focus of the data is on successful and thoroughly detailed sanctions gleaned from the available public records on the SEC and DOJ websites.

The prominent spike in the data values during the late 2000s is not a sign for concern25; the dataset follows one of two themes: many small-value sanctions in one year or only a few very large-value sanctions in one year. This is merely the usual static of any statistical analysis and does not indicate sudden changes in enforcement or overuse of the FCPA.

Finally, in 1988 and 1998, the FCPA was amended by Congress. In 1988, amendment altered the legal standards for violating the law, ensuring that those who willfully or consciously disregard the law could still be found at fault for their actions.27 A decade later, in 1998, the law was further amended to extend the scope of the FCPA.28 As both amendments altered the how the law can be enforced, they necessarily changed the underlying data. However, there is no suggestion that this had a tangible effect on whistleblowers coming forward with information on violations of the FCPA.

Section C. The FCPA Has Collected Enormous Amounts of Money for the U.S. Treasury

As previously noted, the DOJ handles criminal prosecutions under the FCPA, while the SEC, although it has a mandate for criminal cases, nearly always retains the civil prosecutions.

Over the past four decades, the money collected through FCPA prosecutions has totaled over $16.2 billion. Of this amount, the DOJ has accounted for over $9.4 billion, while the SEC has accounted for over $7.2 billion.

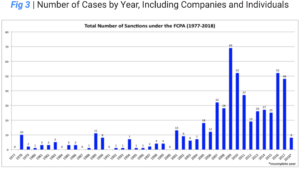

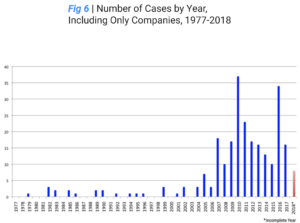

Fig 3 demonstrates a net increase in the total number of full prosecutions under the FCPA since 1977. Despite the variation, from regular changes year over year as cases can take significant time to work through the investigation and prosecution phases, there is a gradual overall increase in the number of successful cases.

This data demonstrates that, along with the growth of globalized trade and relations, fraud detection and the related methods have grown. The implication is that the law has kept up with international practices, allowing the U.S. to ensure transparency, accountability, and ethical business practices. While the data does not account specifically for cases with whistleblowers, given the FCPA whistleblower provisions and the data here, one can assume that the FCPA and its programs holistically work and have improved to meet the demands of an increasingly globalized world, allowing the U.S. to prosecute crimes that may initially seem to be less than directly under US jurisdiction.

Fig 3 demonstrates a net increase in the total number of full prosecutions under the FCPA since 1977. Despite the variation, from regular changes year over year as cases can take significant time to work through the investigation and prosecution phases, there is a gradual overall increase in the number of successful cases.

This data demonstrates that, along with the growth of globalized trade and relations, fraud detection and the related methods have grown. The implication is that the law has kept up with international practices, allowing the U.S. to ensure transparency, accountability, and ethical business practices. While the data does not account specifically for cases with whistleblowers, given the FCPA whistleblower provisions and the data here, one can assume that the FCPA and its programs holistically work and have improved to meet the demands of an increasingly globalized world, allowing the U.S. to prosecute crimes that may initially seem to be less than directly under US jurisdiction.

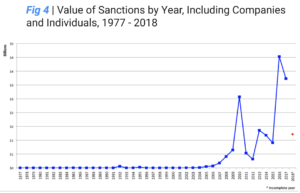

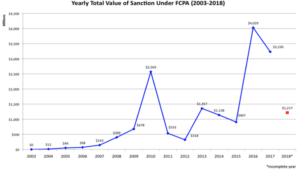

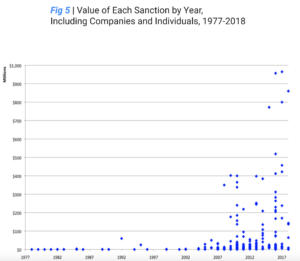

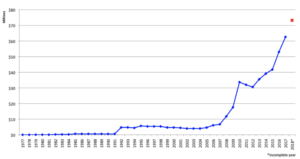

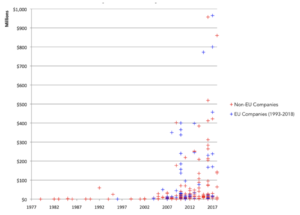

A similar trend is prevalent when observing the total value of sanctions rendered under the FCPA. Fig 4 demonstrates that over time, yearly sanction totals grew. Enforcement of the FCPA is most frequently related to violations by companies, which is accordingly the focus of this report. Sanctioning companies, like the overall enforcement of the FCPA, has seen a rise in quantity and value. Although the SEC frequently charges numerous individuals as co-defendants along with related charges against a company, resulting in s seemingly higher number of cases against individuals defendants, there are more occurrences of corruption by companies overall.

`

It is clear that the U.S. Treasury benefits from a significant and consistent increase in funds as a result of the strong enforcement of the FCPA. Growing numbers of cases, growing value of the sanctions obtained, and growing numbers of whistleblower tips have all helped create a cycle of accountability for those who attempt to gain illicit profits through bribery and corruption.

The increased incentives for whistleblowers have led to an unprecedented number of investigations and greater recoveries.

— Former Principle Deputy Assistant Attorney General Stuart Delery, Department of Justice (2012)

(i) Looking at FCPA Prosecutions of Companies: The following figures demonstrate the data from FCPA prosecutions solely of companies, from both the DOJ and the SEC.

Fig 6 demonstrates a rapid increase in successful prosecutions against companies in the 21st century, revealing just now rapidly the FCPA’s efficacy has grown over time.

[When the SEC] whistleblower program was being set up, many in the securities bar … worried that the program would undermine internal compliance efforts … [but it has] the opposite effect … Companies are beefing up their internal compliance and making it clear … internal reporting will be treated seriously and fairly. And most in-house whistleblowers that come to us went the internal route first.

— Former Chairman Mary Jo White, Securities and Exchange Commission, remarks at the Securities Enforcement Forum, Washington DC (2013)

Fig 7 | Rolling Average** of Value of

Sanctions, Including Only Companies

Fig 7 illustrates the exponential rise of the average sanction amount over time. This graphic reveals that, not only is the number of sanctions rising, but the values are growing, as well, over time. This means the FCPA is allowing the DOJ and the SEC to both fine corrupt companies and confiscate large amounts of monies. Such actions are expanding as the Act ages and efficacy increases. The increase from 2017 to the incomplete year of 2018 notes that in simply the first six months of the year, the FCPA is proving to be more effective than ever before with the growing count and value of sanctions. These are funds brought into law enforcement at no cost to taxpayers. This exemplifies characteristics of good governance.

Fig 8 | Number of Cases by Year,

Including Only Companies

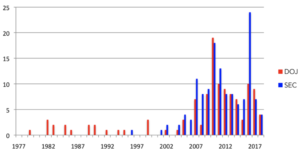

From the data released by the SEC and DOJ, it appears the FCPA is enforced against companies fairly equally, over time, between the two agencies. As Fig 8 reveals, the DOJ issued most early sanctions against companies under the FCPA, but by the 2000s, the SEC prosecuted companies at a greater rate than the DOJ. Both agencies are upholding their enforcement mandates under the law and have seen an increase in sanction issuance over time. The data and press releases offered by both the SEC and the DOJ websites reveal ever-increasing cross-agency cooperation in the investigation and prosecution of corrupt actions under the FCPA. Despite the seemingly higher prevalence of SEC levied sanctions, the agencies are both working, often together, to uphold the FCPA.

(ii) Looking at FCPA Prosecutions of Individuals:

The following figures demonstrate the data from FCPA prosecutions solely of individuals, from both the DOJ and the SEC.

Fig 9 | Number of Cases

by Year, Including Only

Individuals, 1977-2017

Fig 10 | Rolling Average of

Number of Cases by Year,

Including Only Individuals,

1977-2017

Fig 9 and Fig 10 reveal the same trend for individuals as companies: The number of successful prosecutions under the FCPA increases over time. While the individuals charged per year appears to vary to a greater degree than with companies, there is an overall increase in number of issued sanctions and a general upward trend. This indicates that the law is helping enforcement agencies keep up with the increasingly globalized and internationally-focused world. The FCPA allows for the SEC and the DOJ to charge individuals and companies for international corrupt acts so long as they are under U.S. jurisdiction, and it does so effectively with soaring numbers.

The rolling, or moving, average is a line which calculates a succession of averages derived from successive segments (in this case the years) of a series of values (in this case the number of sanctions or the value of those sanctions), depending on the chart. This figure is a “widely used indicator in technical analysis [that] helps smooth out [the line] … by filtering out the ‘noise’ from random … fluctuations. It is a trend-following, or lagging, indicator because it is based on [the] past.”31 Because a lagging indicator illustrates a particular pattern or trend, it was pertinent as to this analysis which seeks to show the pattern over decades of enforcement of the FCPA whistleblower law.

[A whistleblower] “admission often brings… [an] added measure of public accountability.”

— Chairman Mary Jo White, Securities and Exchange Commission, remarks at the Securities Enforcement Forum, Washington DC (2013)

Section D: International Tips Received

International Reach

The effectiveness of the FCPA is driven in large part by the extensive allowances for international jurisdiction by U.S. law enforcement authorities. As such, the FCPA helps ensure transparency, accountability, and ethical business practices worldwide.

The FCPA is often known as the law used to prosecute bribes paid abroad by companies directly and indirectly connected to the United States. The law does something that the average layperson may think is not possible: The FCPA establishes U.S. jurisdiction for bribes paid in foreign countries by foreign nationals to foreign government officials. This means that the FCPA is applicable even if bribes are paid in a foreign country and the whistleblower is a foreign national, which makes it both particularly effective and gives it international reach.

International whistleblowers can add great value to our investigations.

— Former Director Andrew Ceresney, Division of Enforcement, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, remarks made at the Sixteenth Annual Taxpayers Against Fraud Conference (2016)

Additionally, some mistake the fact that the law targets companies that issue stock (in the American market) for the fact that it covers only American companies. However, as the law also covers international corporations traded on foreign stock exchanges, that permit U.S. citizens to invest though the process known as American Depositary Receipts or “ADRs.”

According to the SEC, “[a]n ADR is a security that represents shares of non-U.S. companies that are held by a U.S. depositary bank outside the United States.” This means that U.S. individuals can invest directly, and the FCPA explicitly gives the SEC and DOJ jurisdiction over such actions. In fact, today “there are more than 2,000 ADRs available representing shares of companies located in more than 70 countries.

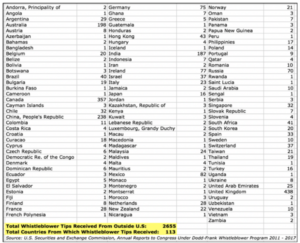

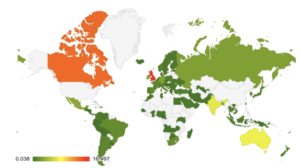

International Tips to SEC

Enforcement of the FCPA is a priority for the SEC, which has a specialized unit to deal with FCPA cases. The agencies report their enforcement actions separately, but the SEC has been particularly transparent since a reform of its whistleblower program approximately a decade ago. According to the SEC, since 2011, a total of 2,655 whistleblowers from 113 countries, outside of the U.S., have filed claims under whistleblower reward provisions. See Fig 11, below. As previously noted, all whistleblowers are eligible to receive between a minimum of 10% and a maximum of 30% of the total amount recovered after a successful prosecution. In that time, over $30 million has been paid to non-U.S. citizens who reported bribes paid overseas, among other crimes, through no cost to taxpayers and exclusively from fines collected from the prosecuted parties.

Fig 11 | Tips Received from Outside of the U.S., by the SEC

[An] award of more than $30 million shows the international breadth of our whistleblower program as we effectively utilize valuable tips from anyone, anywhere to bring wrongdoers to justice. Whistleblowers from all over the world should feel similarly incentivized to come forward with credible information about potential violations of the U.S. securities laws.

— Sean X. McKessy, Chief of the SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower, Press Release: SEC Announces Largest-Ever Whistleblower Reward (2014)

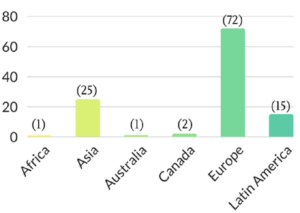

Fig 12 | International Tips Recieved by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 2011 – 2017, by Frequency

It is clear that those in charge of implementing the law understand the importance of whistleblower tips to their ongoing law enforcement success. In 2017, the SEC confirmed that high-quality whistleblower tips and allegations have triggered over 700 pending or ongoing investigations.

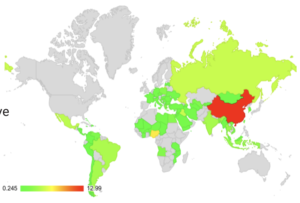

Section C. Mapping the FCPA Violators

Companies registered throughout the world have been prosecuted under the FCPA by U.S. law enforcement authorities.

Fig 13 | International Cases by

Region, 1977-2018

Section D. Looking at Top Violators

Bribes occur worldwide with the vast majority concentrated in Asia and Latin America. As Fig 14 and Fig 15 illustrate, a handful of countries see the greatest frequency for where the bribe occurs, with China leading for both company and individual prosecutions.

Fig 14 | Companies have

been prosecuted for

FCPA violations in the

following countries:

Fig 15 | Individuals have

been prosecuted for

FCPA violations in the

following countries:

Together, China and Nigeria account for over 20% of all locations of bribes by companies prosecuted by the U.S. government under the FCPA.

The top 50% of countries where bribes by companies were prosecuted by the U.S. government under the FCPA account for 87% of the total such prosecutions. Bribery of government officials is concentrated in some locations more than others, and the U.S. government has the power and knowledge to bring these criminals to justice.

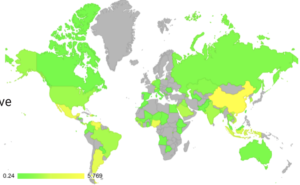

Section E: The FCPA in Europe

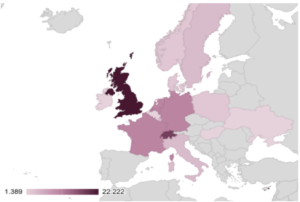

Companies prosecuted for violating the FCPA are located throughout Europe. This map shows the frequency of cases for each country in the region. Note that this includes only companies, not individuals, prosecuted under the FCPA, as the information on the individuals is tied to where the bribe occurred, rather than the nationality of the criminal.

Fig 16 illustrates the country of registration of companies prosecuted under the FCPA in Europe, based on the percentage of all Europe-based cases. European registered companies only comprise approximately 12% of all successful cases.

Crucially, most of the Europe-based cases came out of a handful of the approximately 50 countries in Europe, identified in the tables below. The map reveals that companies registered in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany, France, and the Netherlands are violating the FCPA at the highest frequency. It is worth noting that these five countries belong to the European Union. Moreover, approximately half of all European FCPA cases were EU-based companies. This suggests that there is still far to go with ensuring that companies do not engage in bribery and other corrupt practices, and it highlights the importance of the FCPA’s international law enforcement mandate.

Fig 16 | Companies

have been prosecuted

for FCPA violations in

the following countries

in Europe:

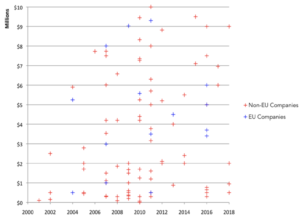

(iii) Looking at the value of monetary sanctions from FCPA Prosecutions of Companies in Europe

Fig 17 | Monetary Sanctions by Year, 1977-2018

Fig 18 | Close-Up of Montary

Sanctions by Year, 2000-2018

PART III:

A. Introducing the Data

The importance of whistleblower tips to successful prosecutions by the SEC is also demonstrated by an analysis of SEC awards to whistleblowers who report crucial information for successful prosecutions. This data includes not just the FCPA, but other laws enforced by the SEC as well. While the publicly-available information released by the SEC does not distinguish between FCPA cases and prosecutions under other laws, the FCPA is a major focus of the SEC. Moreover, it is reasonable to assume that behavior by the SEC’s investigatory and law enforcement agents are somewhat similar among a variety of different legal violations.

An approximate five year span between 2012 to 2018 includes 125 distinct prosecutions with documented and publicly-available whistleblower award proceedings.38 Of these cases, 42 resulted in whistleblower awards. As some cases included several whistleblowers, these 42 cases resulted in 58 total awardees.

In contrast, during this same time period there were 83 cases in which a whistleblower petition for award resulted in the complete denial of any award to a whistleblower. Note that additionally, 31 individual claimants were denied while other whistleblowers in the same case were given awards. The courts and the SEC are clearly looking carefully at whistleblower petitions and ensuring that only the most deserving are granted a reward.

From these cases, whistleblowers were awarded at least $259,400,000 overall. However, the lack of complete data, as a result of redactions and missing documentation, precludes any estimation of the total number of sanctions obtained by the government in these cases, and therefore also any clear understanding of the percentage of the reward given to these whistleblowers (apart from a few cases in which the exact amount was specified). Considering that over $250 million has been awarded to whistleblowers in those five years, who are restricted to a maximum of 30% even in the very best of circumstances, we can know that the SEC has brought significant funds into U.S. government coffers by halting illegal activity with the help of whistleblowers.

B. The Importance of Whistleblowing

The data paints a picture of the crucial nature of whistleblowers to these prosecutions. The most common reasons cited in SEC award decisions for why a whistleblower should receive a reward was that the whistleblower prompted the investigation, led to the successful prosecution, or otherwise provided original information to the government. Moreover, the documents also show that whistleblowers are often credited and therefore deserving of a reward as a result of the unreasonable delay and hardship caused to them, voluntarily offering information to another federal agency and so halting additional illegal activity, or providing ongoing assistance which saved significant government resources.

Additional reasons cited in these documents to justify providing rewards to whistleblowers include: that the violation was hard to detect; that the whistleblower was a company insider; that the whistleblower’s information significantly contributed to or helped to end the investigation; that the whistleblower provided independent knowledge or analysis by the whistleblower; or that there was significant or notable retaliation endured by the whistleblower as a result of their brave decision to come forward.

C. Whistleblowing and the FCPA

In 2017, a whistleblower was awarded more than $4.1 million for stepping forward with information despite the risk he would suffer retaliation for his bravery.

This whistleblower exemplifies much of what we know about how information is kept secret and how illicit profits are made. A “former company insider,” he both alerted the SEC about a criminal enterprise “and continued to provide important information and assistance throughout the … investigation.”39 This original information was critical for the SEC to even know that a violation of the law was occurring.

Yet his concerns also reflect the types of worries by the right person with the right information – that the laws wouldn’t be enough to protect him after he stepped forward. As a “foreign national working outside the” United States, the SEC award determination notes that the whistleblowers’ concerns that American “employment anti-retaliation protections” may not be meaningful outside of U.S. borders. As a result, the financial reward provides important motivation; it incentivizes those with original insider information to come out of the shadows.

In 2014, the SEC announced what was then its largest-ever award to a whistleblower: over $30 million.40 The SEC noted that this individual “provided key original information,” and was thus a crucial component for halting this ongoing crime. While the SEC maintained the confidentiality of the whistleblower, the agency did disclosure that the whistleblower was living in a foreign country.41 As a result, this was necessarily a violation of the FCPA.

Whistleblowers from all over the world should feel similarly incentivized to come forward with credible information about potential violations of the U.S. securities laws.

— Former Chief of the SEC’s Office of the Whistleblower, Sean X. McKessy (2018)

D. What we know, and what we don’t know, about this data

It is crucial to maintain the strict confidentiality and anonymity of the whistleblowers to protect the safety of each whistleblower and to ensure that whistleblowers remain incentivized to come forward in the future. At the same time, however, this makes it difficult for researchers; to collect sufficient data and analyze the full breadth of the effects of the FCPA, more data is often needed.

For example, Part 2 of this report discussed data which included information as to the relevant government law enforcement agency (SEC or DOJ), the nature of the criminal activity, and the fact that such illicit profits were made in violation of the FCPA. In addition, this data included key information on the amount obtained for the U.S. Treasury through the judicial process. However, a lack of data precludes us from understanding which cases included whistleblowers, and to what extent. Moreover, Part 3 of this report focused on whistleblower claims for rewards to the SEC. This data included the relevant agency (in this case, solely the SEC), and so the presumption that the majority of these cases were civil prosecutions, whether the whistleblower’s claim for a reward was successful or not the reasons for the whistleblower’s reward determination and so an understanding of the reasons why the whistleblower was crucial to the case (when given a reward), and the approximate amount of money awarded to the whistleblower.

However, a lack of data as to whether the whistleblower was international or domestic precludes us from understanding which cases are violations of the FCPA, and which are violations of other laws enforced by the SEC. Moreover, documentation made public does not include related action awards, where the whistleblower’s information was used for another case or with another agency, as well as further sanctions clawed back by the government from the criminals, which could in some circumstances substantially increase the reward for the whistleblower (as a percentage of total sanctions obtained by the government in cases which relied on the whistleblower’s information).

Yet, while this may limit analysis of the FCPA, it is crucial to bear in mind that, first, the FCPA’s effectiveness is well-established with existing data and evidence, and second, the confidentiality of the whistleblower is absolutely essential for the continued success of the FCPA, as discussed in Part 1C.

E. A Snapshot of 2018

We can also learn a lot by what is happening in just the last six months. NWC compiled a snapshot of all notices of covered actions by the SEC cases, regardless of the law at issue, in which whistleblowers were involved.42 This data is particularly useful as it covers all cases investigated and prosecuted by the SEC and involving whistleblowers where the SEC believes that a whistleblower (or several whistleblowers) may have a valid claim for a reward. The data also details whether a complaint has been filed or the case has been settled and the amount of sanctions either brought in or to be brought in by the government through each case.

In just six months, the SEC has brought in at least $449,489,571 through 24 whistleblower-involved cases. The average case brought over $18.7 million in fines.

If each of these were an FCPA case, this data would indicate that at least 24 foreign whistleblowers may be entitled for between $1.21 and $3.63 million (between 10% and 30% for each case).

These figures prove that the SEC’s whistleblower program works and is necessary for effective prosecution. While these cases are not necessarily prosecutions for violations of the FCPA, the program analyzed here is the same used by some FCPA whistleblowers. The general effectiveness of the program parallels the reasonable expectations of whistleblowers’ influence on successful FCPA prosecutions.

The whistleblowers who bring wrongdoing to the government’s attention are instrumental in preserving the integrity of government.

— Former Principle Deputy Assistant Attorney General Stuart Delery, Department of Justice (2012)

PART IV:

Conclusion

The FCPA is a key that unlocks U.S. law enforcement’s ability to address corruption worldwide. Much of the Act’s success rests on worldwide investigative cooperation and whistleblowers, insiders who are willing to speak out. As this report has shown, violations of the FCPA occur all over the world, but are especially concentrated when it comes to companies in specific countries. Knowing the profound influence that this law has beyond U.S. borders, this data serves as a reminder that whistleblower programs must be protected if we hope to root out corruption.

Provisions that extend whistleblower awards to foreign nationals are extremely valuable in fighting corruption; the vast majority of FCPA violations happen far from U.S. soil, but effect the American economy and community.

Whistleblowers are powerful tools for detecting fraud and corruption. The FCPA is continuing a movement toward a world in which corruption does not go unnoticed or unpunished. Whistleblowers are crucial to this process. Supporting protection and reward programs for brave individuals who blow the whistle should be of the utmost importance to anyone seeking to implement effective anti-corruption laws, such as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (“FCPA”).

Acknowledgements

Maya Efrati is the Policy Counsel for the National Whistleblower Center. Her work focuses on strengthening democratic institutions, promoting anti-corruption and good governance reforms and advocating on behalf of increased whistleblower protection. She earned her J.D. from the University of Michigan Law School, simultaneously earning her M.P.P. from the University of Michigan Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy. In a legal capacity, she previously worked for the Michigan Innocence Clinic, the Center for American Progress, FairVote, and Represent.Us. Before law school, she also worked for a large Congressional campaign, AFSCME Council 36, and the Peres Center for Peace, among others.

Jacob R. Gardner was a Summer 2018 Intern at the National Whistleblower Center in conjunction with his participation in the Wisconsin in Washington, DC program through the University of Wisconsin – Madison. He is a current Pre-Law student at UW – Madison and studies Political Science and Communication Arts. Mr. Gardner has previous experience with higher education institutional leadership and campus-based sexual/dating violence prevention and survivor support education.

Stephen M. Kohn serves pro bono as the Executive Director of the National Whistleblower Center, and is a founding partner of the whistleblower law firm of Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto in Washington, DC. He has represented whistleblowers since 1984, successfully setting numerous precedents that have helped define modern whistleblower law and obtained the largest reward ever paid to an individual whistleblower ($104 million for exposing illegal offshore Swiss banking practices). He is widely recognized as the leading U.S. authority on whistleblower laws, and helped draft whistleblower provisions in the Sarbanes-Oxley, Dodd-Frank, and Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Acts. He teaches a seminar on whistleblower law at Northeastern University of Law, and has published numerous books on whistleblower law, including The New Whistleblower’s Handbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Doing What’s Right and Protecting Yourself (Lyons Press, 2017), the seminal guide on whistleblowing. He currently represents confidential and anonymous clients in North America, Asia, Africa, and Europe, many of whom filed FCPA cases.

Additional thanks to: Julia S. Malleck, Communications Fellow, for assistance with design; Kelsey Condon, Associate Attorney at Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto, for legal guidance; law clerk Angelica Duron, and interns Ben Kostyak, Caroline Buthe, and Michael Ellis, for assistance compiling data.

Download the PDF version of the report with reference section here.